The Belgicka Boys

The third group of the Boys arrived in the UK from Prague on a series of five flights in February and March 1946.

The Central British Fund had spent the autumn of 1945 trying to bring orphaned children from the American and British occupied zones of Germany to Britain. One group had arrived Southampton but the departure of another group from the Belsen-Hohne Displaced Persons’ Camp had been blocked by the Committee of the Liberated Jews of Bergen-Belsen.

In the New Year, the CBF turned its attention back to Prague. The story of the third group of the Boys illustrates the enormous problems that survivors still faced in eastern Europe a year after the liberation of Auschwitz.

THE CHALLENGE OF LIBERATION

The overwhelming majority of the third group had been born in Czechoslovakia. The 148 children included 67 girls.

The majority of the Boys had returned to Czechoslovakia from the concentration camps. Many of them were near starvation at the moment of liberation and were extremely ill in the weeks that followed. For a number of them convalescence took months and delayed their return home. The return journey was also set with perils and difficulties as the way home led across a devastated war zone.

For Jewish survivors, the liberation brought new dangers and complications. The majority had no relatives and no money. Most came home to find that neighbours or strangers were living in their homes and received a hostile and often violent welcome.

Many of Boys waited for weeks in the hope that their families would return home and in the third group there were a number who were fortunate enough to be reunited with siblings and cousins. Once they realised that the remaining members of their families were not coming home, they decided to move to Bratislava and Kosice in Slovakia, and to the capital Prague. In the three cities there were Jewish committees that offered survivors help and assistance. The committees were funded by the United Nation Relief and Rehabilitation Administration (UNRAA) and the aid organisation the American Joint Jewish Distribution Committee (JDC). Many of the Boys were cared for in Jewish children’s homes.

WHY PRAGUE?

It was no accident that three of the four groups of the Boys left from Czechoslovakia.

Prague was liberated by the Red Army on 9 May 1945, but the Soviet Union was not a legal occupying power as it was in Germany. Between 1945 and the communist takeover in 1948, Czechoslovakia was an independent country ruled by a coalition government of liberal democrats and communists who organised their own affairs. The new Czechoslovak Government was in control of relief operations and immediately set up the Czechoslovak Office of Relief and Rehabilitation.

A key member of the new government was Jan Masaryk, whose father Tomas Masaryk had been the president of pre-war Czechoslovakia from 1918-35.

From 1925, Jan Masaryk had served as ambassador in London and had been Foreign Minister in the wartime Czechoslovak government-in-exile. At the end of the war, he became the new Czechoslovak Foreign Minister.

His appointment was a significant one, as after the Holocaust, thousands of Jews passed through Czechoslovakia fleeing from Poland. Those who chose to leave headed for the American-occupied zones of Austria and Germany.

Masaryk was committed to helping the survivors along what was known as the Bricha escape route. Masaryk helped get survivors into the American occupied zones with the help of Israel Gaynor Jacobson, the Prague representative of the JDC, who worked tirelessly to smooth the refugee's journey.

Joseph Schwartz, the European Director of the JDC was convinced that Jews had no future in central and eastern Europe and, despite the fact that it was JDC policy to support existing Jewish communities, he actively helped the Bricha and illegal immigration to Palestine through Czechoslovakia. He also worked closely with the Central British Fund and its head Leonard Montefiore in order to find a safe home for child Holocaust survivors stranded in Czechoslovakia.

Although the new Czechoslovak government was happy to help survivors who passed through the country, they were not so accommodating towards their own Jewish citizens. The new post-war Czechoslovakia was a far more nationalist country than it had been before the war. Citizenship was only given to those who had declared themselves Czech or Slovak in the 1930 census. Property restitution was hindered by the fact that those who had not registered as Czech or Slovak in the 1930 census were not eligible for government assistance. This meant that even children with a surviving parent or older sibling were in a precarious situation.

After the end of hostilities Czechoslovakia expelled 3 million Germans who had previously been Czech citizens. This move was sanctioned by the Allies at the Potsdam Conference in the summer of 1945. Pre-war ethnic Hungarians were also deprived of their Czechoslovak citizenship. The Jews who had declared themselves as Jewish in that census were in a precarious legal situation. Antisemitism was also rife and in September 1945, there was a pogrom in the Slovak town of Topolcany. No one was killed in the violence, but 47 Jews were badly wounded.

After appeals from aid workers in Prague, the CBF stepped in to help.

THE BELGICKA ORPHANAGE

The third group of the Boys are often referred to as the Belgicka Boys as they were gathered together before their departure in the Home for Jewish orphans on Belgicka Street in Prague, just as the first group on the Boys had been. The orphanage played a significant role of the majority of the Boys immediate post-war experiences. To find out more click here.

Some of the younger children spent the months after the liberation in the children’s homes south of Prague that were run by the Christian philanthropist Presmyl Pitter. The homes cared for both German and Jewish orphans. Thirty-seven of the youngest members of the Windermere Boys had also spent time in Pitter’s homes. To find out more click here.

JOURNEY TO THE UK

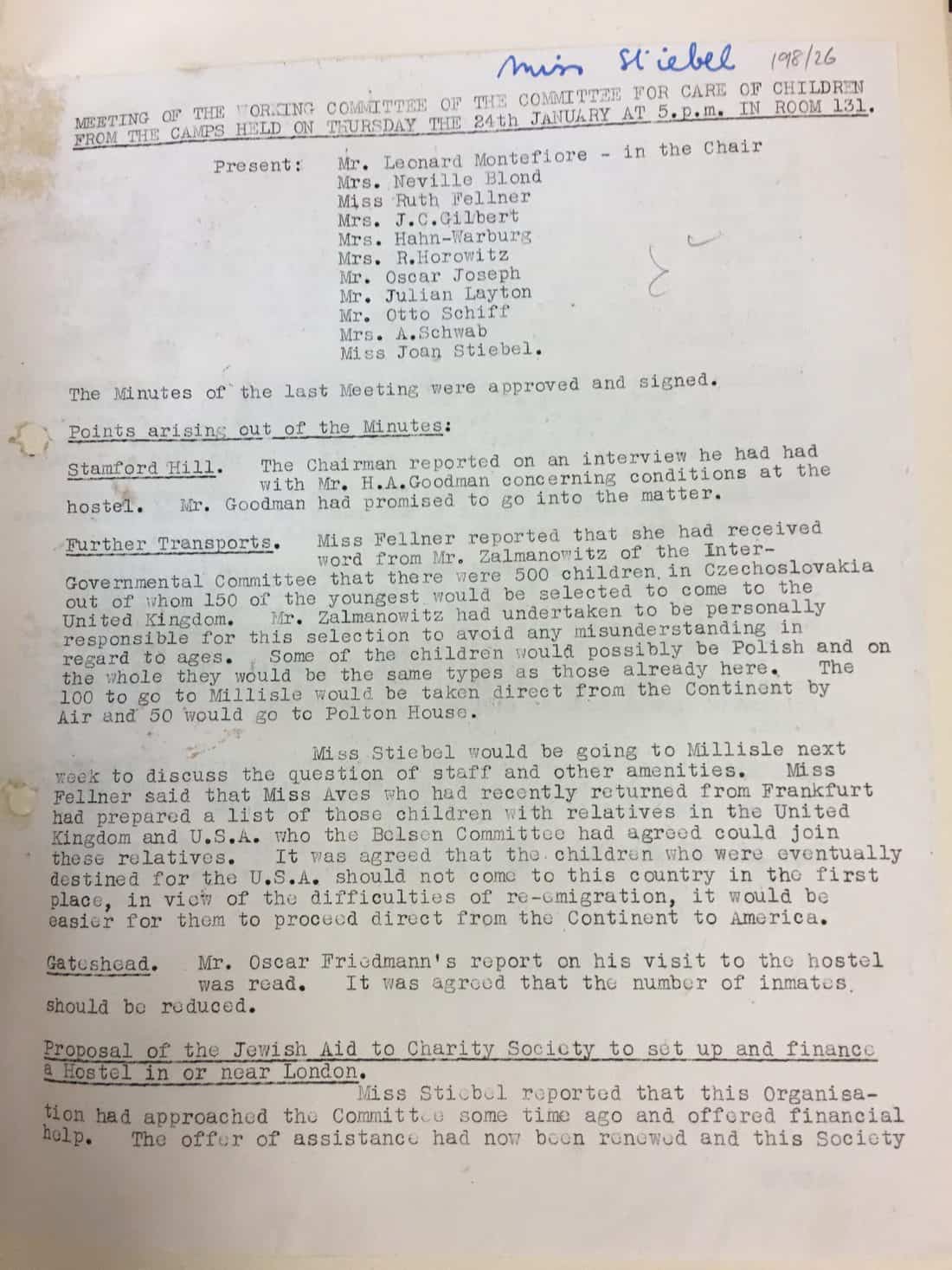

The Central British Fund’s Ruth Fellner flew to Prague to oversee the departure of the third group and returned on the last flight with one of the groups of the Boys. On the ground Madame Holubova, the head of the Jewish Refugees Committee in Prague organised bringing the group together.

The British Ambassador Sir Philip Nichols came to see the Boys off. David Herman recalls “the large crowd of dignitaries on the tarmac who had come to see us off...I boarded the plane, a British Air Force military Dakota....Most of us were sick on the plane, as this was our first experience of flying. The journey took more than four hours and we arrived at Northolt military airport...It was raining hard.”

Herman’s group flew to RAF Northolt near London, others were taken to Prestwick airport, near Glasgow in Scotland, and some to Northern Ireland.The papers of the Committee for the Care of the Concentration Camp Children held in London’s Metropolitan Archives show that the JDC paid the transportation costs.

After the second group of the Boys had refused to be transferred from the reception centre in Wintershill Hall to the farm school at Polton House in Scotland, it was decided that it would be better to fly a group of children directly to Scotland in February 1946. Another flight went directly to Belfast, in Northern Ireland where the children were cared for in the Millisle training farm. These farms were supposed to prepare the Boys for kibbutz life in the Palestine Mandate, where the majority of the Boys hoped to settle.

On the flight to Northolt were some of the younger members of the boys who were among the youngest children left alive in Auschwitz at the liberation. They had been selected for medical experimentation as they were, or were believed to be, twins. The youngest children were taken to the Weir Courtney hostel in Surrey.

On arrival in Northolt, the older teenagers were taken by coach to the Jewish Shelter in the East End of London. Herman recalls the group’s first meal at the shelter, where “many of us hid our plates under the table as we had done in the orphanage so that we could get second helpings.”

They stayed for a few days before being taken by train to Montford Hall in Lancashire.

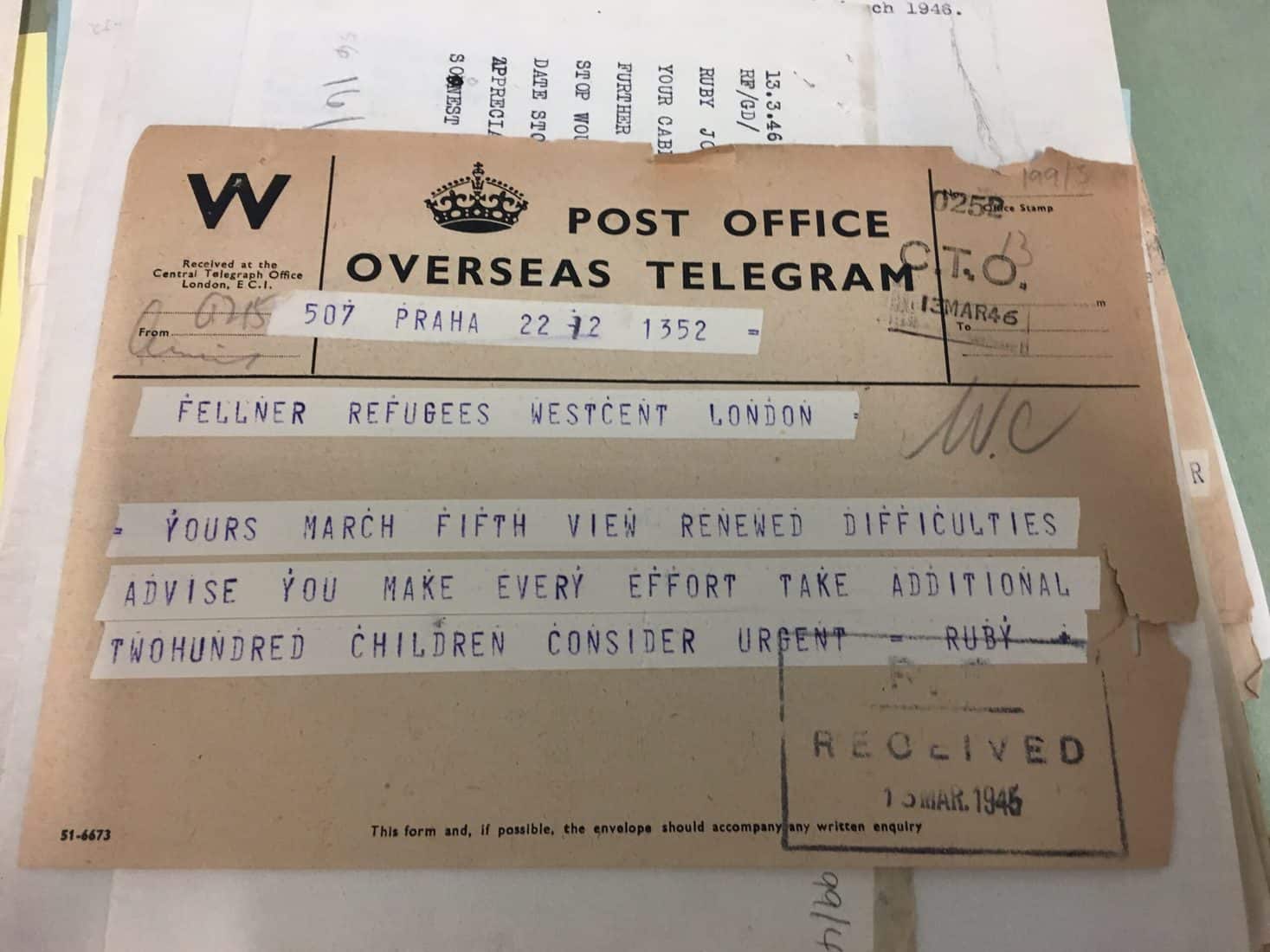

Immediately after the third group of the Boys arrived, Fellner received telegrams from Prague urgently asking for a further group of children to be brought to the UK. This would lead to the fourth group of the Boys.

The Boys:

- Abish, Sylvia

- Abraham, Ruzena

- Adler, Arthur

- Alter, Herman

- Berkovic, Sipora

- Berkovitz, Samuel

- Berman, Bella

- Blum, Julius

- Bogner, Ervin

- Brandstein, Issac

- Braunsteinova, Blanka

- Brody, Simon

- Bucci, Andra

- Bucci, Liliana

- Buncel, Erwin

- Chaimovic, Feige

- Chaimovic, Karel

- Czimet, Aranka

- Czuker, Jan

- Deutsch, Ignac

- Deutsch, Zoltan

- Diamantstein, Julius

- Dub, Ruzena

- Eckstein, David

- Ehrman, Alzbeta

- Emmer, Manfred

- Farkas, Arnold

- Farkas, Efraim

- Farkas, Eva

- Farkas, Jacob

- Farkas, Salomon

- Feige, Marija

- Fischer, Berta

- Fischer, Cecilia

- Fisher, Marketa

- Fixler, Adolf

- Freilichova, Josefa

- Fried, Desidier

- Friedman, Arnost

- Friedman, Hedvika

- Friedman, Hedi

- Friedmann, Alexander

- Friedmann, Fritz

- Frischmann, Ladislav

- Frischmann, Vilem

- Frydman, Simon

- Galkacova, Susanne

- Gerstein, Josef

- Gross, Alexander

- Gross, Roza

- Gruen, Hugo

- Gruenberg, Vilem

- Gruenfeld, Herman

- Hamburger, Julius

- Herman, David

- Herscovic, Israel

- Herz, Peter

- Himmelstein, Jan

- Hoffman, Adolf

- Hopf, Arnost

- Ickovic, Etelka

- Ickovic, Cevenka

- Jakubovic, Chaim

- Jakubovic, Zlata

- Josef, Marketa

- Kalecker, Nelly

- Kaufmann, Bernard

- Klein, Andrej

- Klein, Gisella

- Klein, Marija

- Klein, Tomas

- Kleinmann, Vojtech

- Kochen, Ellek

- Kraus, Favla

- Lacker, Ruzena

- Liberman, Alfred

- Liberman, Magda

- Luger, Salamon

- Luger, Herman

- Luger, Mendel

- Marcovic, Miroslav

- Markovic, Zdenka

- Markovic, Moric

- Markovicova, Serena

- Marmelsteinova, Vilma

- Marton, Alzbeta

- Mauskopf, Eva

- Mauskopf, Erwin

- Moscovicova, Edita

- Moskovicova, Gisella

- Neuman, Jiri

- Neumann, Emil

- Oesterreicherova, Luisa

- Offner, Dolly

- Palkowic, Armin

- Perl, Manci

- Pinkas, Benjamin

- Reil, Bernard

- Rezmocicova, Ester

- Rosenberg, Helena

- Rosenberg, Mendel

- Rosenberg, Bella

- Rosenberg, Chaim

- Roth, David

- Rothman, Benjamin

- Rothman, Leopold

- Rothschild, Herman

- Sabova, Berta

- Sabova, Marcia

- Safar, Dora

- Salamon, Tibor

- Samuel, Charlotte

- Schaechter, David

- Schwartz, Alfred

- Schwimmer, Edita

- Simkievic, Edek

- Simkovic, Samuel

- Slomovic, Chaskel

- Slomovic, Jolana

- Slomovic, Ruzena

- Slomovic, Helena

- Slomovicova, Ruzena

- Speigel, Estvan

- Steinberg, Josefina

- Steinmetz, Moses

- Stern, Edita

- Stern, Eliska

- Stern, Eva

- Stern, Melanie

- Stern, Mirjam

- Stern, Judita

- Swartz, Rushka

- Teichmann, Mendel

- Teichner, Dorothea

- Traub, Hanka

- Traub, Eva

- Vegh, Maurice

- Waldmann, Joseph

- Weinberger, Samuel

- Weingarten, Edita

- Weiss, Imrich

- Winkler, Emil

- Zelig, Josef

- Zelikovic, Helena

- Zimlichman, Fani

- Zweig, Stepanka

- Zweig, David

Source: Arolsen Archives.

Stirin Castle, one of Pitter's children's homes south of Prague. Photo: Rosie Whitehouse

The former Belgicka Orphanage in Prague. Photo: Rosie Whitehouse