The Paris Boys

The fourth group of the Boys left Prague in May 1946 and arrived in the UK on 11 June. The group of just over a hundred children included 40 girls.

The overwhelming majority of the children who made up the fourth group were from the Carpathian Mountains which had been a remote corner of the Austro-Hungarian Empire and was home to a unique multi-ethnic society which, until the First World War, shared languages and mystical views and worked alongside each other harmoniously. After World War 1, the heart of the region became the most easterly part of Czechoslovakia.

THE CHALLENGES OF LIBERATION

After their liberation, the Boys from the Carpathians decided to return home from in search of loved ones but were met with hostility from neighbours. The war had intensified the ethnic divisions and resentments in the Carpathians but peace also brought new challenges for the returning survivors. When the Red Army arrived, it was Soviet policy to incorporate the region into the Soviet Union and the Boys found themselves dealing with an increasingly hostile Red Army. The story of the fourth group illustrates how the rescue of Jewish children from eastern Europe had changed from rescuing them for a war zone and then from increasingly xenophobic governments to a Cold War story.

When Carpathian Ruthenia was annexed by the Soviet Union from Czechoslovakia after a rigged referendum in July 1945, the vast majority of the Jews who lived in the area before the Holocaust, who were not only very religious, but many were Zionists, found themselves on a collision course with Stalinism.

There were around 15,000-20,000 Carpathian survivors and many of them decided that there was no future for them in the former homeland. The vast majority of the fourth group of the Boys fled westwards before the new Soviet borders were sealed in the autumn of 1945.

Their priorities were to earn a living and find somewhere to live. This meant that they headed for towns like Bucharest, Budapest, Bratislava, Kosice and Prague where the Jewish humanitarian organisation, the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee funded Jewish committees were offering survivors assistance and help in tracing relatives.

Many of the Boys found refuge in western Czechoslovakia and especially in Silesia. However, unlike the Jews who had lived in Silesia before the war, the Carpathian Jews were not assimilated and spoke Yiddish. The local population resented their presence.

At the core of the problem was that in the 1930 census, 93% of all Carpathian Jews had declared their nationality as Jewish. Acquiring Czech citizenship was thus a major issue that became more problematic as 1945 turned into 1946 and there was an increasing danger that the survivors would find themselves stateless, face repatriation and be unable to rebuild their lives in Czechoslovakia.

It was increasingly clear to the Boys that the challenges of rebuilding their lives in eastern Europe was no longer a possibility and emigration was now their priority.

PREPARATION

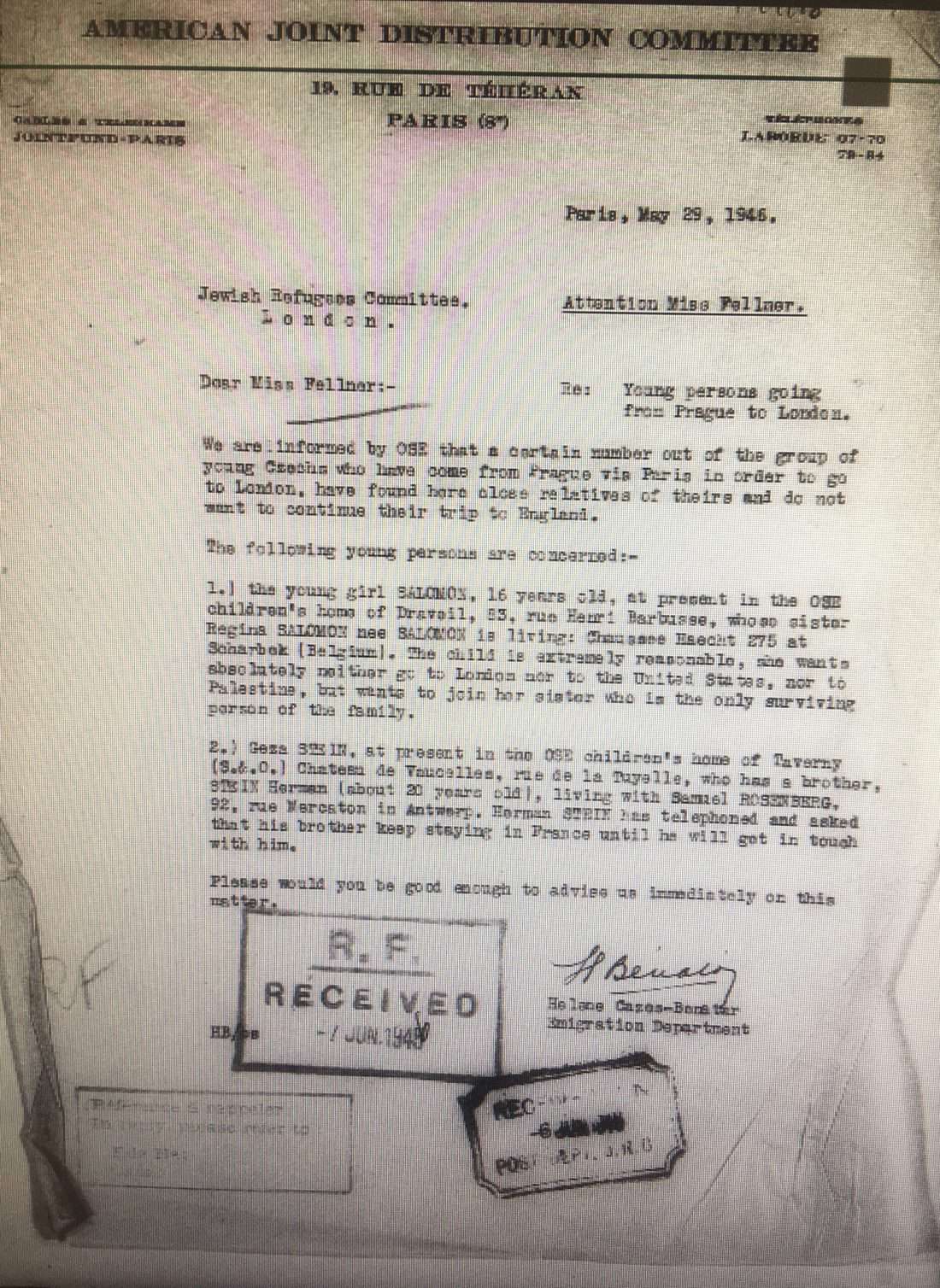

Ruth Fellner first alerted the Central British Fund to the plight of the Carpathian child survivors in November 1945. The desperate position that the Carpathian children found themselves in is reflected in Fellner’s correspondence with the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee officials in Prague.

Fellner reported to the CBF on 24 January 1946 that 500 children, without Czechoslovak citizenship, were in desperate need of assistance as they were likely to be repatriated to the Soviet Union. Documents in the London’s Metropolitan Archive show the deep concern that aid workers on the ground had for the fate of the Carpathian Jews, whom they feared could be expelled from Czechoslovakia “overnight”.

If repatriated, they would not be allowed to practice their religion or could face imprisonment as Zionists. Their repatriation was later prevented, but only after the intervention of the American ambassador.

WHY PRAGUE?

Attitudes on the ground in Prague played an important part in how and why the Boys of the fourth group were able to leave the country. Key was the attitude of the Czech government.

During the Second World War, many of the governments of occupied Europe, among them the Czechoslovak government, had based themselves in London after the outbreak of the Second World War. Many leaders of the Czechoslovak Jewish community also fled to Britain. Throughout the war, the British Jewish community and exiled Jewish leaders campaigned to highlight the suffering of Europe’s Jews. Those leaders knew the principal members of the Central British Fund and had worked with them on the pre-war Kindertransports. It was thus natural for them to come together after the Holocaust to help the surviving children who found themselves in Czechoslovakia at the end of hostilities.

The post-war Czechoslovak government was, from 1945-48, committed to assisting Jewish survivors and helping them leave the country. The Czech government was keen to encourage Jewish emigration which smoothed the way for the Central British Fund to bring the Boys out of Czechoslovakia.

All this created the right environment on the ground in London and in Prague which enabled the Boy’s rescue and journey to Britain.

Meir Stern, one of the Boys from Munkacs, recalled hearing about the transport from an advertisement put up in a synagogue in Prague. He says that the Jews from the Carpathians, who were living in Prague, were a very tightly knit group, so news of the transport would have quickly travelled among them.

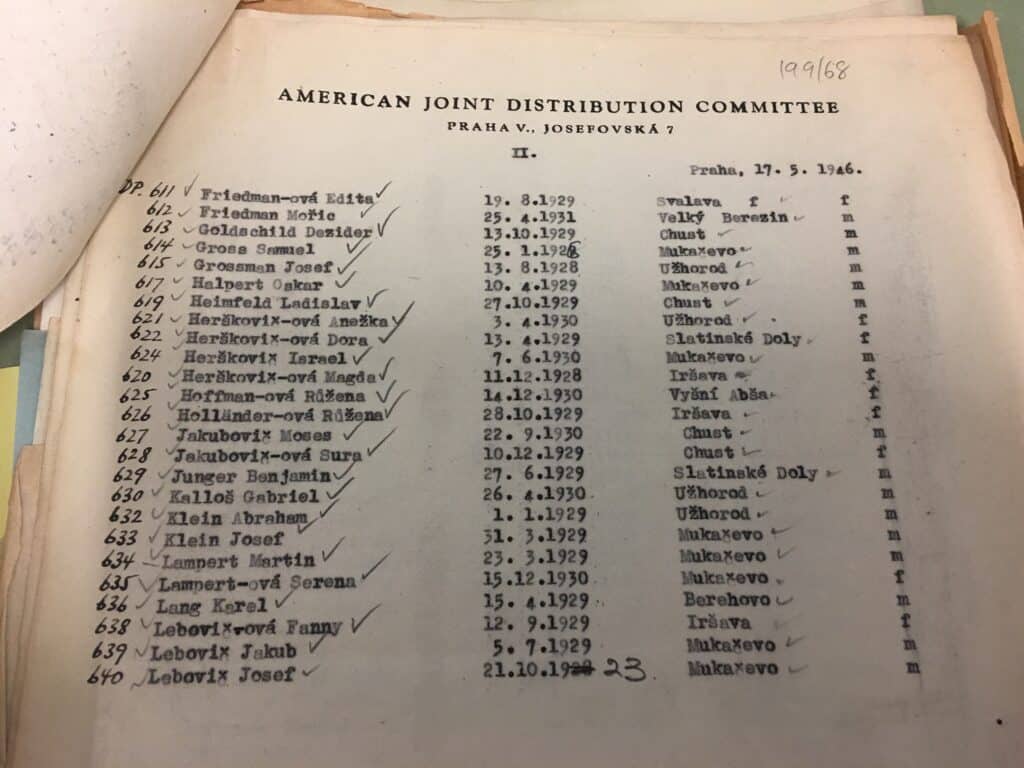

The list of the children travelling to the UK was drawn up by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, who played a vital role in caring for Holocaust survivors after the war. They paid the Boys’ travel costs.

JOURNEY TO THE UK

They traveled in two groups from Prague to Paris and then sailed together from Dieppe to Newhaven on the south coast of England.

The first group flew from Prague and crash landed in Brussels. They continued their journey to Paris by train. It was then decided that the rest of the Boys would travel by train. The original intention was for the group to travel in special cars attached to the Orient Express that ran from Prague to Paris but the four cars were too heavy for the engine. They were then attached to a repatriation train heading for Brussels. Stern recalls that as the train travelled through Germany, they threw stones out of the window as the train passed through the villages and towns. Every time the train stopped they gathered more stones. Stern says they were given American rations and Camel cigarettes and when they arrived in Belgium, they were taken on a day trip to Brussels.

They then continued their journey to France, where the group spent some weeks in the suburbs of Paris. The children’s care was overseen and paid for by the American Jewish Joint Distribution Committee, who had their European headquarters in Paris in rue de Teheran in 8th arrondissement.

The group was split up and some children stayed at the Oeuvre de Secours aux Enfants hostel in the Chateau de Vaucelles in Taverny, just north of Paris. Significantly this was the home to part of the group known as the Buchenwald Boys, which included Elie Weisel and in the village of Draveil at Les Glycines 83 boulevard Henri-Barbusse, near present day Orly airport. The Boys were offered the opportunity to stay in France but preferred to come to the UK.

ARRIVAL IN THE UK

The group sailed from Dieppe to Newhaven in June 1946. The children had never seen the sea before and many were sick on the Channel crossing.

Of 106 children set off from Prague but only 103 arrived in the UK. Two ran away and two of the young people who made the journey to Paris discovered during the journey that they had surviving relatives. A brother who had accompanied the children in the hope he might make it to UK was then given a visa.

After they arrived in Newhaven they were given tea and then put on a train for London. They arrived at Victoria Station and from there they were taken to the Jewish Shelter in Mansell Street in the East End.

But the moment they put their suitcases down, a letter arrived on Fellner’s desk from the JDC begging her to take 50 to 100 more children. Fellner replied she could not commit to taking them until the situation at her end had “cleared”.

Fellner’s reply reveals the anger felt by CBF officials that some of the survivors who arrived in June had been older than 18 years and had surviving brothers, sisters and even parents in Czechoslovakia.

More importantly, the children’s arrival had stretched the CBF’s resources to breaking point. A lack of accommodation had forced them to house the children in the Jewish Shelter, which was a home for destitute adults.

Despite the JDC’s pleas, hundreds of Carpathian child survivors remained in Czechoslovakia. After June 1946, there were no more transports of children brought to the UK by the CBF. The fifth group was brought independently by Rabbi Solomon Schonfeld.

The Boys:

- Abisch, Jindrich

- Abraham, Alzbeta

- Abraham, Martin

- Abraham, Salomon

- Abrahamovic, Samuel

- Bandel, Mechel

- Basch, Ignac

- Basch, Freida

- Basch, Ruzena

- Beckman, Ida

- Berkovic, Frantisek

- Birnbaum, Anna

- Blobstein, Arnost

- Blobstein, Ludvik

- Brandt, Lazar

- Davidovic, Martin

- Edelstein, Lazar

- Eisdoerfer, Vera

- Farkas, Jan

- Feldmann, Alzbeta

- Feuerstein, Herman

- Fried, Artur

- Friedman, Edith

- Friedman, Moric

- Goldschild, Desider

- Gross, Samuel

- Grossman, Josef

- Gruenwald, Ester

- Halpert, Oskar

- Handelsmann, Malvina

- Heimfeld, Ladislav

- Herskovic, Magda

- Herskovic, Herman

- Herskovic, Dora

- Herskovic, Israel

- Herzkovic, Aneska

- Hofman, Ruzena

- Hollander, Ruzena

- Jakubovic, Sara

- Jakubovic, Moses

- Junger, Benjamin

- Kallos, Gabriel

- Kest, Frida

- Klein, Avraham

- Klein, Josef

- Lampert, Moshe

- Lampert, Serena

- Lang, Karel

- Lazarovic, Charlotte

- Lebovic, Fani

- Lebovic, Jakub

- Lebovic, Josef

- Lebovic, Otakar

- Lebovic, Ruzena

- Liebermann, Moric

- Lipschitz, Desider

- Lipschitz, Evzen

- Markovic, Irena

- Mermelstein, Simon

- Moskovic, Lily

- Noe, Etelka

- Noe, Salomon

- Papir, Gita

- Perl, Josef

- Polak, Vojtech

- Prizant, Dora

- Rosenberg, Vilem

- Rosenthal, Richard

- Rosenthal, Alexander

- Rubin, Viola

- Schwarz, Magarita

- Stern, Vera

- Stern, Tamas

- Stern, Herman

- Stern, Eliska

- Stern, Meir

- Sternova, Magda

- Sunog, Arnost

- Svimmer, Chaim

- Szebov, Moric

- Tennenbaum, Vilem

- Veis, Helena

- Vermes, Erika

- Weinberger, Irena

- Weisova, Alzebeta

- Weiss, Bernard

- Weiss, Pirozka

- Weiss, Regina

- Weiss, Sari

- Weisser, Herman

- Weisser, Michael

- Wunzinger, Janko

- Zelikovic, Josef

- Zelkovic, Fanny

- Zelkovic, Hersch

- Zelkovic, Vili

- Zelmanovic, Ludwig

- Zelmanovic, Fanny

- Zelovic, Etel

- Zisovic, Luisa

- Zuckermandl, Rene