Bulldogs Bank

The hostel known as Bulldog’s Bank was in the rural village of West Hoathly in Sussex in southern England.

It was, for one year, the home to six of the youngest members of the Boys - three girls and three boys. All of the six had been in the Theresienstadt ghetto in Czechoslovakia, where they had been liberated by the Red Army on 8 May 1945. The children arrived at Bulldog’s Bank on 15 October 1945.

The hostel was funded by Foster Parents Plan, now Plan International USA, and the children’s care was overseen by the psychoanalyst Anna Freud. Plan was founded in 1937 by the British journalist John Langdon-Davies and refugee worker Eric Muggeridge to care for children whose lives had been disrupted by the Spanish Civil war but it soon turned to caring for children across war-torn Europe.

THE HOUSE

The Central British Fund were given use of the house by Mrs Ralph Clarke, wife of the MP for East Grinstead, Sussex, who was a friend of Anna Freud.

High up on a hill, it had a stunning view and enormous garden. The children had two rooms each, one for the boys and one for the girls, with an adjoining bathroom. There was a large nursery, staff rooms, a veranda and a sun terrace.

The house is currently a private home.

THE BULLDOG’S BANK STORY

Anna Freud and Sophie Dann wrote a detailed account of life at the hostel, An Experiment in Group Upbringing (1951) in which life at Bulldog’s Bank is described in detail. It is a unique book and the only description of young child Holocaust survivors of its kind.

According to the authors, all six of the children had been in the Ward for Motherless Children in Theresienstadt. “They had no toys and their only facility for outdoor life was a bare yard.” They had all lost their mothers in the first years of their life and had been repeatedly moved. They had no knowledge of family life. The children’s names were changed in the account, but they are easily identifiable.

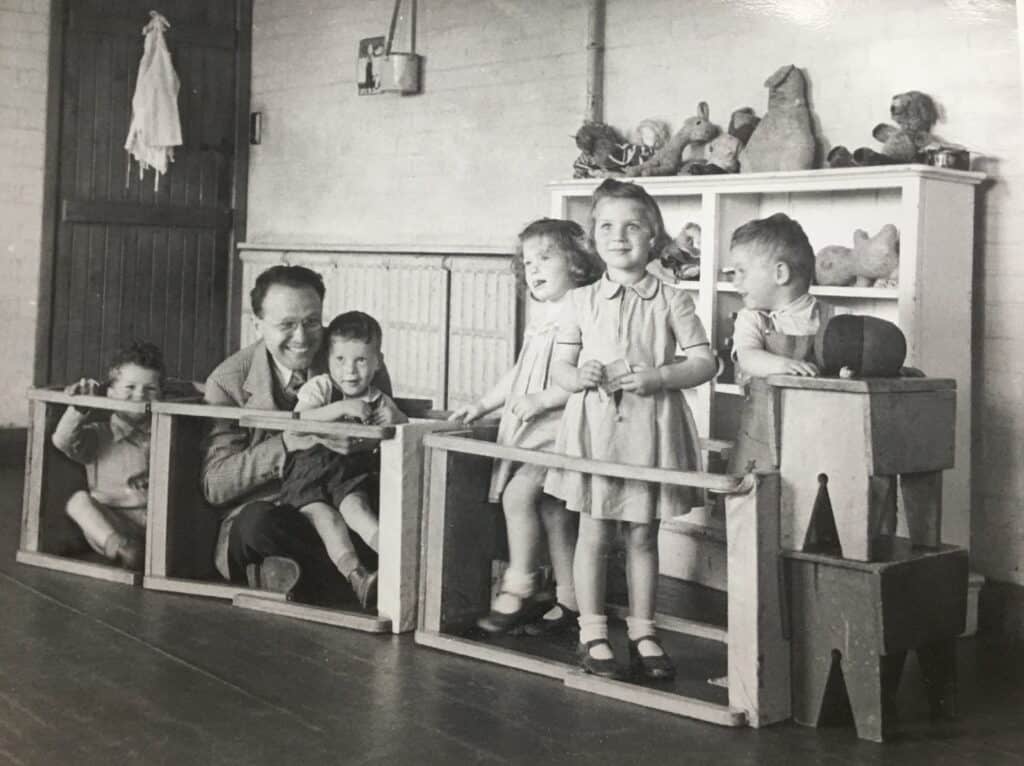

Caring for the children was a challenge according to Freud and Dann and the children reacted badly to being moved from the reception camp in Windermere. “They showed no pleasure in the arrangements which had been made for them and behaved in a wild and restless, and uncontrollably noisy manner.”

They destroyed all of the toys provided and damaged the furniture. They showed a cold indifference towards the staff. There was nothing personal in their aggression and indifference they wrote. It was simply that they perceived the world as hostile and threatening. The six used biting in the way toddlers tend to bite as a weapon.

They treated the adults with complete indifference and in anger hit, bit and spat at them. They were aggressive especially when one of their group was separated due to illness

The children spoke a mixture of German and Czech. “Stupid fool” was one of their favourite German expressions. They are often described by Freud and Dann as “malicious”.

Martha Wenger, who had cared for the children in the Ward for Motherless Children in Theresienstadt survived the war. She wrote to Dann from the Dagendorf Displaced Persons camp in the American occupied zone of Germany.

In the letter she said that, ‘Peter’ was “fearlessly naughty” and that there was such a shortage of staff in Theresienstadt that the adults had no time to play with the children. She also said that she was especially close to Judith Auerbach, who she said had had pneumonia in ghetto.

It was noted on arrival that: “The childrens’ positive feelings were centred exclusively on their own group. It was evident that they cared greatly for one and other and not at all for anybody or anything else.” They were upset by being separated even for a few moments. The staff found this a challenge as it was hard to treat them as individuals. They refused even to be separated for a nap when tired or ill - even for a treat.

In the group they all had equal status. They were extremely considerate to each other’s feelings and made sure each of them was treated the same way. They helped each other by carrying coats on outings and making sure they were all safe.

They were in fairly good physical condition but “pale, flabby, with protruding stomachs and dry, stringy hair, cuts and scratches on their skin tending to go sceptic”. They were given cod liver oil and other vitamins.

After a year at Bulldog’s Bank the children begin to build ties with the adults and show them empathy but the ties between them remained the strongest tie of all. ‘Ruth’ was the only one to build a mother-like relationship with Gertrude Dann. She had had a close attachment to Martha Wenger in Theresienstadt.

Soft toys played a key role in rehabilitation and all the children had a doll or teddy bear that they kept close until books and writing letters took their place, as they developed an interest in the outside world, in the spring of 1946.

The six were bad eaters and at first refused any food that was not starchy. Indeed, they had little interest in food. They craved sugar and put it on everything. The sugar was supplied by the Foster Parents Plan as there was strict rationing in the UK.

They had no understanding of city traffic or flowers and animals. The only animal they had seen was a dog, which was considered an object of terror and they screamed when they saw one. Another object of fear was a feather, but Freud and Dann had no idea why this was the case. They were also fearful of vans.

The six quickly caught up with the level of nursery education for their age group. The first nursery rhyme they learned in English was Ba-Ba Black Sheep, which they sang when they were happy and for guests.

At first, learning English was a point of stress and confusion. They clung to the German negation nicht and then put it with the English not-nicht, and for an entire year they continued to use meine for mine.

By the summer of 1946, however, they had that stopped speaking German and showed no recognition of the language. As adults many of them expressed anger that they had not only lost their mothers but also their mother tongue.

The children were reunited by the psychologist Sarah Moscowitz when she wrote her book Love Despite Hate: Child Survivors of the Holocaust and Their Adult Lives in 1987. They have remained in touch ever since.

The Boys

We are building our online archive. If you have further information or material on this hostel, please contact ’45 Aid Society or fill in the form below.

The Staff

Bulldog’s Bank was staffed by sisters Sophie and Gertrude Dann from the Hampstead Nursery, which was another of Anna Freud’s projects, where they had cared for children from the East End of London during the Blitz. The sisters were pre-war refugees from Germany. Sophie was a nurse and Gertrude a teacher.

The children were brought by train by Maureen Wolfson, who had looked after the children in Windermere. Alone with five of the children (one remained in hospital), she said it was one of the most stressful journeys of her life. She stayed for a few weeks at Bulldog’s Bank until she was replaced by Judith Gaulton, a relief worker. The children were upset by this change.