Sunday 8th May, 2016

Barnet Copthall Stadium, Hendon, London NW4 1RL (same venue as 2015)

To Book Complimentary Tickets & Parking go to: yomhashoah.org.uk

Sunday 8th May, 2016

Barnet Copthall Stadium, Hendon, London NW4 1RL (same venue as 2015)

To Book Complimentary Tickets & Parking go to: yomhashoah.org.uk

The Annual ‘45 Aid Society Chanukah Party will be held in London on

Sunday 6th December

at 3pm in West Hampstead.

Contact us for Details

The ‘45 Aid Society Annual Memorial Service will be held in September 2017

Date and Location – to be announced – check back here

To be held in Wembley, North London on 1 May 2017

Reception 4:30pm & Dinner 6:00pm

Tickets in Advance Only.

Contact: max.kim@hotmail.co.uk

Sunday 22 May 2016, 4pm

Menorah Synagogue, 198 Altrincham Rd, Wythenshawe, Manchester M22 4RZ

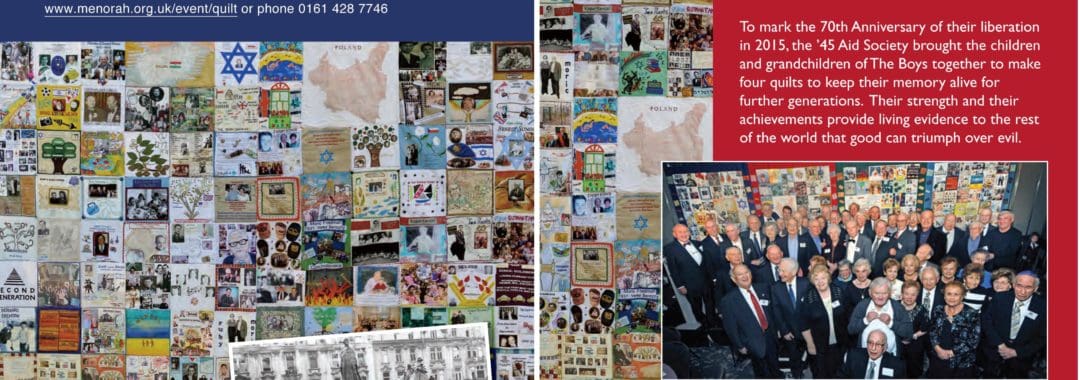

The story of The Boys and the creation of the Memory Quilt presented by Sue Bermange & Julia Burton.

For further information go to: menorah.org.uk

Tickets £7.50.

Survivors and their families should contact the Menorah Cultural Director, Vicki Garson on 07715 011146 before buying tickets

Join us for the 2016 Reunion Dinner on Mon 2 May 2016 at London Wembley.

The evening will feature a tribute to the work of the ‘45 Aid Soc. President, Ben Helfgott.

Tickets go on sale Now at £60 per head via Kim Stern max.kim@hotmail.co.uk

Come and help us to celebrate the work of the Society’s President.

DON’T MISS IT!

The London Jewish Museum is going to be holding talks on the stories behind the Memory Quilt and the 45 Aid Soc Survivors

Venue: London Jewish Museum

Date: Every Wednesday at 2pm during the Memory Quilt exhibition

Details:www.jewishmuseum.org.uk

Liberation came to us in many ways and varied circumstances. Some, I imagine, were strong enough to be about to see the Germans run for their lives or saw them surrender. It must have been a sight to see, an emotion of a lifetime to experience.

I was flat on my back, ill, pretty well on my way out and certainly past caring. Needless to say I saw none of it.

Instead, I woke up one day to find myself in a hospital bed. A bed with linen, clean linen, I might add and people caring for me. Caring for ME!

It was not long before I was able to get up and found myself convalescing in a children’s home in Theresienstadt. My first HOSTEL.

I shared a room with four or five other boys. This of course was heaven when you consider the crowded conditions that I had been used to until then.

Erna, our matron, had two girls to help her and soon we became one small family. Some of us were more energetic than others, but we were all getting gradually used to becoming individuals again. I began to discover that I am a person in my own right – quite a revelation after years of propaganda about “vermin” and “parasites”, etc.

One could not leave Theresienstadt without a permit, add to it that it was a garrison town, life was inevitably somewhat restricted, a good thing in a way as it introduced us into normal life in a city in a gradual way.

The arrival at Prague was quite an experience. The friendliness and hospitality of the Czech people is something I, for one, shall never forget. It was in Prague that I went to a circus and to a cinema for the first time as a free person.

Then England by courtesy of R.A.F. Bomber Command. There were no seats or “mod-cons”. We sat where we could. On the floor, on boxes, anything at all. The R.A.F. men acting as kinds of stewards communicated with us in sign language. We spoke no English.

Carlisle aerodrome and then by coach to Windermere. Windermere, what a delightful place! On arrival I was shown into a tiny room with a bed, chest of drawers and wardrobe. A room all to myself! Has anyone ever lived so luxuriously?

It was a particular time of, certainly, my life when there could have been no gift more precious. For the first time in years, in my short life, I would have the luxury of a room ALL TO MYSELF. I could have danced in the street for joy. I could and would have except for a small “technicality”.

Well, the clothes in which we arrived were suspect – from a cleanliness viewpoint – and so it had been planned to have new clothes waiting for us on arrival. There was a hitch. We arrived first. No clothes, except for underwear. Well, we were issued these and nought else. Since we could not wear our old clothes, underwear was all we had. I just danced, metaphorically speaking, in my new room.

Windermere, my second hostel-home, was where a group of friendly people one of whom, at least, Alice Goldberger, is here tonight, helped me and the others in various ways; teaching English, etc. This was where I began to make friends with England and the English.

It was a happy time for me, I had the proximity of so many friends, sharing a dining room with them and participating in a variety of activities and yet being able to retire to the luxury of my PRIVATE room. I cannot recapture the wonder of it in words sufficient to do the feeling justice. However, I have no doubt that those who shared this experience with me will know precisely what I mean.

Windermere – “Wondermore” – as I like to call it, stands out for me for what it was, apart from its renowned natural beauty. It was my own reintroduction to a new life as an individual where living was no longer on the level of the animal’s instinct for survival but things of the spirit, of sight, sound and touch began to matter. Wonderful things were happening in “Wondermore”. A happy, happy time.

Three months or so went by very quickly and it was time to move on yet again.

Scotland. Darleith House was about three miles from the village of Cardross in Dumbartonshire. It was in the style of a mansion set in its own extensive grounds with a rhododendron-flanked drive leading to it from the keepers lodge about a quarter of a mile away.

It would be quite easy, again, to become ecstatic about the beauty of the setting and the general splendour of the place, which as my third hostel was about to become my new home, but to do so would be no more that to state a fact.

Here I must pause and say something for the people who planned all this for us. It was obvious that a lot of effort, accompanied by a generous breadth of imagination went into finding these places for our benefit. I feel that a deep humanity coupled with an understanding of our need to be in lovely surroundings as an antidote to the ugliness that we had encountered in our lives hitherto, was the visionary motive in all this.

To these people, whoever they are, MY SALUTE.

I settled down to study and my English began to improve, and although Polish and Yiddish were still used a lot, English gradually began to take over.

I recall an incident which amused us at the time.

Teachers would come up from Dumbarton for various subjects. One, a Mr Smith, taught us English. He was very good with us and we often shared a joke. Our English was beginning to be passable. One day, during an English lesson Mr Smith heard someone talking and it was not in English. “Boys”, he said, “unless you speak English only you will never learn the language properly”.

Up stood one of the boys and his reply, which although somewhat cheeky, was taken in good part as it demonstrated that we were making strides towards speaking the new tongue.

Here is what he said: “Mr Smith, you see, I have to speak Polish sometime because I am in the habit of telling myself jokes. If I tell them in English I shall not understand what they are about”.

Mr Smith seemed pleased with the effort.

Cardross was more a less akin to life in Windermere with the same aims, pursuits and above all its country setting.

Glasgow was different, and here I began to work, still living communally in a hostel. I was learning a trade and studying in my spare time. Gradually city life was something I was taking in my stride and soon feeling confident of being able to cope for myself. I moved with a friend from the hostel and into “digs”. Life has come full circle. I began a “normal” life.

Henry Green

We know that the average chance of survival in the camps was low, and that it varied through time. For example, it must have fallen substantially during the evacuation period which preceded the end of the War.

I seemed to be acutely aware of these changing chances of survival. As the evacuation period proceeded I regarded my chance as, objectively, getting smaller and smaller and indeed approaching zero. Yet, subjectively, I somehow did not believe that I would die. This tension between the perceived objective reality of one’s survival chance and the subjective refusal to accept it was illustrated by an incident I can still vividly remember.

We had been marched out of Flossenburg when the camp was evacuated in the face of the approaching Americans. During the march in the direction of Dachau we once had to stop on the road to allow a different column the right of way. You will recall that during those marches the guards had two kinds of arrangement for dealing with stragglers; either a straggler would be shot by the guard nearest to him, or some guards at the rear of the column would be detailed for this work. The second arrangement had been adopted for that other column. Since we now stood still, and our energies were temporarily released from the effort of marching, the extent of the prevailed slaughter forced itself upon us as never before. We silently looked at each other in muted horror as if to say: “at this rate our turn will come any moment”. Yet, subjectively, we probably refused to believe it.

In this particular case, however, the subjective beliefs of most of us were to be justified. Two or three days later the American Army overtook our column of marching skeletons. We were free – quite suddenly we were no longer prisoners whose lives had been at the mercy of any guard, but people who could even rely on the American Army for protection. Quite suddenly the moment had arrived of which we had been dreaming constantly for years but about whose likelihood of arrival we had always been ambivalent. And when the moment arrived we were too exhausted to greet it with the joy it deserved.

Kurt Klappholz

The Almighty and I have had many disagreements in the past, but matters came to a head in the Lodz Ghetto on my twelfth birthday.

My mother conferred upon me the full status of a Barmitzvah boy, as my father was dead and my two elder brothers and two sisters were in other ghettos. In the twilight of every Shabbat, she would talk to me in a most serious fashion about all manner of things; especially about my ancestors (distinguished rabbis and talmudic scholars) and how they personally intervened with the Almighty. Once, when my eldest brother was critically ill, my great-grandfather Rabbi Henoch of Alexander appeared to her in the dead of night and pronounced that my brother would live, contrary to expert medical opinion. I knew of course that I was also a very near relative of the illustrious Gerer rebbe. So my chutzpa grew and grew and I started to demand of the Almighty straight answers. “Why,” I asked “does he let the Nazis throw down sick children from a fourth floor window into lorries to be taken to Auschwitz?”

I worked in a children’s hospital – office boy cum porter and big brother to the sick children. I was the only one in the hospital whom the parents of the sick children would trust with their precious food parcels (saved from their own meagre rations), to be safely delivered to the children’s sick beds.

And so, the Almighty and I grew further apart, till one Sunday morning we parted company. I discovered in an obscure part of the ghetto a fascinating library full of communist literature, Emile Zola’s “Germinal”, “The Communist Manifesto”, and others. The answers were there, loud and clear. My conversation lasted until Friday.

On Friday night, my mother lit the Shabbat candles and we both intoned in Hebrew “Shalom Aleichem Malachei Hashalom” – “Welcome Angels of Peace” – by then, I felt the Shekhina (Divine Presence) in our house. The meal was of course marvellous, Jewish mothers in the ghetto had perfected the art of making gefilte fish and tsimes out of potato peelings. But I eagerly looked forward to the second part of Friday night, the Oneg Shabbat with Jacob.

Jacob was eighteen, thin, tubercular with fiery brown eyes, and a large forehead. He was the leader of a secret Zionist youth group, which met every Friday night, at a factory which made uniforms for the Germans. When Jacob spoke of the Hebrew poets the Divine Presence rested upon him.

“You will all survive and one day see Eretz Israel. The Nazis will perish”, he kept prophesying. If arguing with the Almighty I found difficult – arguing with Jacob was impossible!

Friday night was a happy night.

The Almighty and I have a much better relationship now. I forgive Him his imperfections, and he is I think, quite reconciled to my fallen star, for my children can hardly claim to be the sons of a rabbi. However, on Friday night when my wife lights the Shabbat candles, and we all kiss her Shabbat Shalom, I feel that the Divine Presence cannot be far away

Felix Berger

Necessary cookies are absolutely essential for the website to function properly. These cookies ensure basic functionalities and security features of the website, anonymously.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| __stripe_mid | 1 year | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| __stripe_sid | 30 minutes | This cookie is set by Stripe payment gateway. This cookie is used to enable payment on the website without storing any patment information on a server. |

| _wpfuuid | 11 years | This cookie is used by the WPForms WordPress plugin. The cookie is used to allows the paid version of the plugin to connect entries by the same user and is used for some additional features like the Form Abandonment addon. |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-analytics | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Analytics". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-functional | 11 months | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Functional". |

| cookielawinfo-checbox-others | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Other. |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-advertisement | 1 year | The cookie is set by GDPR cookie consent to record the user consent for the cookies in the category "Advertisement". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-necessary | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookies is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Necessary". |

| cookielawinfo-checkbox-performance | 11 months | This cookie is set by GDPR Cookie Consent plugin. The cookie is used to store the user consent for the cookies in the category "Performance". |

| PHPSESSID | session | This cookie is native to PHP applications. The cookie is used to store and identify a users' unique session ID for the purpose of managing user session on the website. The cookie is a session cookies and is deleted when all the browser windows are closed. |

| viewed_cookie_policy | 11 months | The cookie is set by the GDPR Cookie Consent plugin and is used to store whether or not user has consented to the use of cookies. It does not store any personal data. |

| wordpress_test_cookie | session | This cookie is used to check if the cookies are enabled on the users' browser. |

Functional cookies help to perform certain functionalities like sharing the content of the website on social media platforms, collect feedbacks, and other third-party features.

Performance cookies are used to understand and analyze the key performance indexes of the website which helps in delivering a better user experience for the visitors.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| YSC | session | This cookies is set by Youtube and is used to track the views of embedded videos. |

Analytical cookies are used to understand how visitors interact with the website. These cookies help provide information on metrics the number of visitors, bounce rate, traffic source, etc.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| _ga | 2 years | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to calculate visitor, session, campaign data and keep track of site usage for the site's analytics report. The cookies store information anonymously and assign a randomly generated number to identify unique visitors. |

| _gat_gtag_UA_77414095_1 | 1 minute | This cookie is set by Google and is used to distinguish users. |

| _gid | 1 day | This cookie is installed by Google Analytics. The cookie is used to store information of how visitors use a website and helps in creating an analytics report of how the website is doing. The data collected including the number visitors, the source where they have come from, and the pages visted in an anonymous form. |

Advertisement cookies are used to provide visitors with relevant ads and marketing campaigns. These cookies track visitors across websites and collect information to provide customized ads.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| IDE | 1 year 24 days | Used by Google DoubleClick and stores information about how the user uses the website and any other advertisement before visiting the website. This is used to present users with ads that are relevant to them according to the user profile. |

| NID | 6 months | This cookie is used to a profile based on user's interest and display personalized ads to the users. |

| test_cookie | 15 minutes | This cookie is set by doubleclick.net. The purpose of the cookie is to determine if the user's browser supports cookies. |

| VISITOR_INFO1_LIVE | 5 months 27 days | This cookie is set by Youtube. Used to track the information of the embedded YouTube videos on a website. |

Other uncategorized cookies are those that are being analyzed and have not been classified into a category as yet.

| Cookie | Duration | Description |

|---|---|---|

| CONSENT | 16 years 7 months 26 days 2 hours 8 minutes | No description |

| m | 2 years | No description |